This article is part of a series exploring the reverse engineered inner workings of Downland, a game for the Tandy Color Computer, released in 1983, written by Michael Aichlmayr.

The moving objects in the world of Downland need to know the limits of where they can go. They can’t pass through walls and they can’t fall through floors. The game therefore needs a method to detect whether an object can move through space or is stopped by the chamber’s terrain. And because chambers are made out of irregular shapes, the method can’t use a simple grid as seen in tile-based games.

What Downland uses is a method that detects per-pixel accurate collisions which, while memory hungry, provides the player with fun platforming tricks.

Mr. Clean

When the game draws its graphics, it does it into a frame buffer, a region of the Color Computer’s memory. The computer hardware displays this area as pixels on the screen. To achieve pixel perfect collisions, the game uses a second buffer, which I call the “clean buffer”, which contains a copy of the chamber’s background graphics.

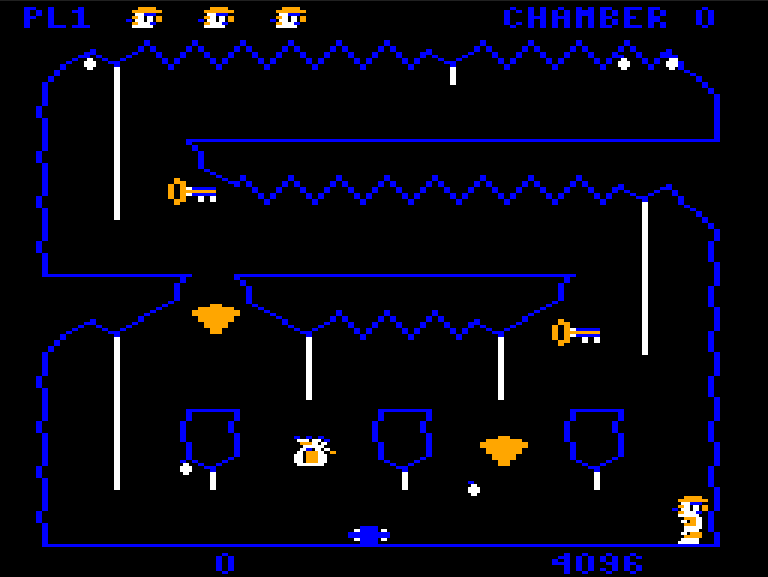

Game’s frame buffer is on the left, the clean buffer is on the right.

The clean buffer is created when the player enters a chamber. First, the game draws the background to the clean buffer. Then a screen wipe transition effect copies the clean buffer to the frame buffer line by line.

After that, all drawing is done on the framebuffer, leaving the clean buffer intact for the game to use.

Memory Use

The frame and clean buffers are unfortunately not free. Both buffers, because of their 256 * 192 one bit resolution, take up 6144 bytes each in memory. This means that only Color Computers with a minimum of 16k of memory can play the game.

Collision Fundamentals

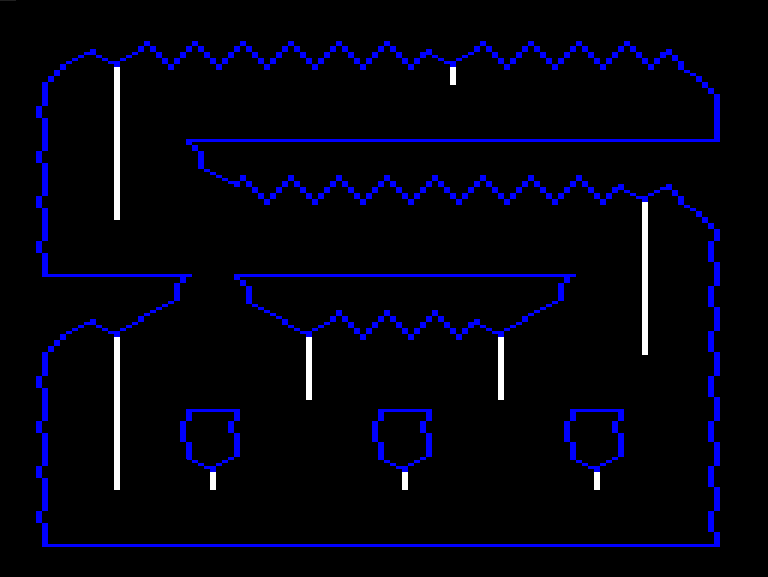

We’ve seen that internally Downland’s graphics are actually 1 bit and look like this:

The same bit patterns that appear blue on screen are used as barriers like walls and floors. Blue pixels have a bit pattern of [0, 1]. To detect collisions when an object is moving, the game reads the pixels around it on the clean buffer. If the pixels at a certain spot are blue, matching its [0, 1] bit pattern, then a collision is detected and the object reacts. The spots checked depend on the type of object and the type of motion.

Let’s go through the different game objects and where they detect collisions.

Drops

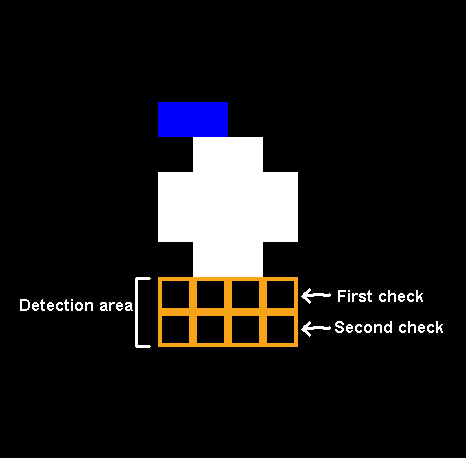

Drops when falling check for floor collisions every update. Using a pixel mask, it checks the four pixels underneath. And because it drops two pixels per frame on the Y axis, it performs another check one pixel lower.

If the drop detects the floor, the drop manager resets the drop into wiggle state and chooses a new random location.

Ball

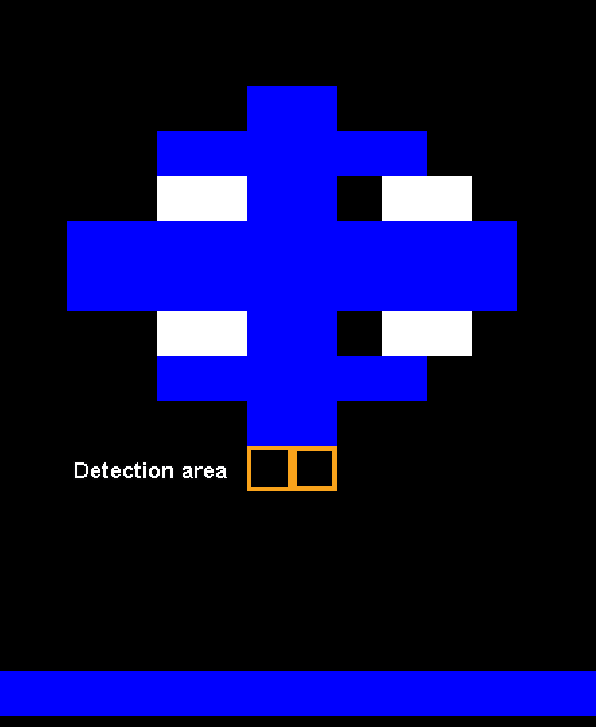

The ball performs two collision checks, one for vertical movement and one for horizontal.

For falling, the game checks for the two pixels underneath the bottom of the ball. It doesn’t need to check any pixels below that like drops because the ball doesn’t fall faster than one pixel per frame.

For walls, the game checks a line across the center of the ball.

The Player

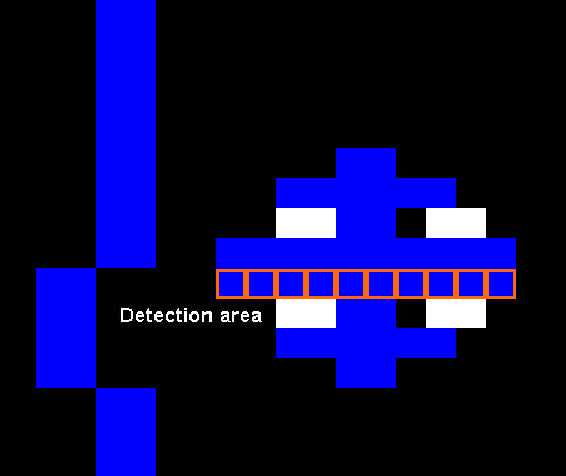

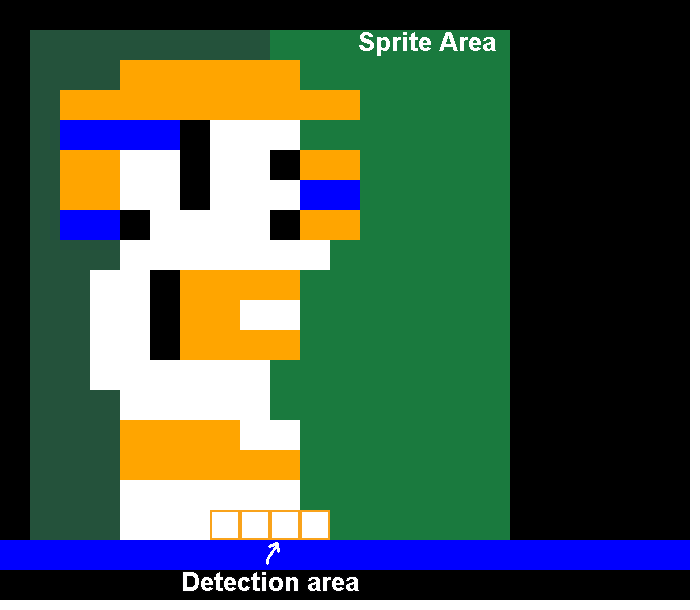

For collisions with the ground, the game checks below the player sprite right in the middle. The check is in the same spot no matter how the player is facing.

For wall checks, it uses the same ground detection area, except one pixel higher. This is used for stopping against walls when running and bouncing off walls when jumping.

Showing The Ropes

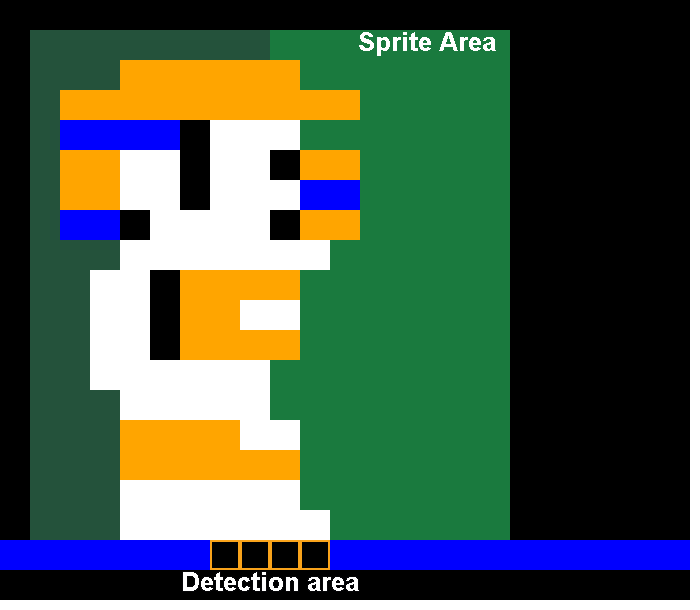

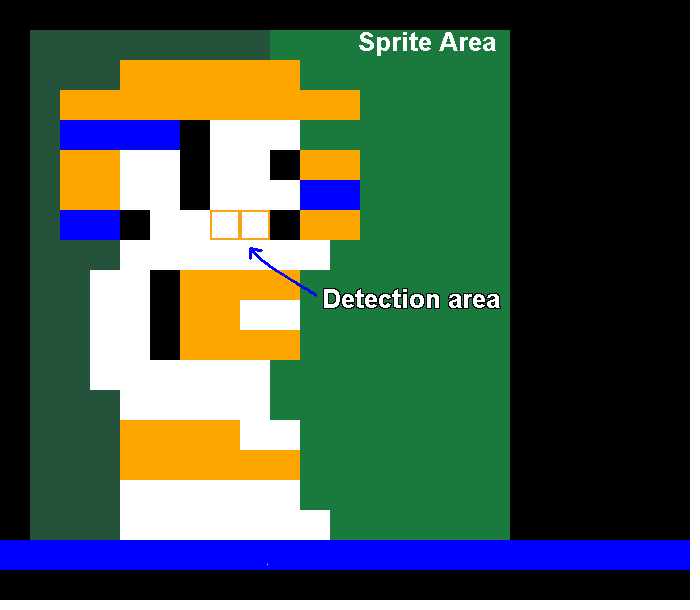

The player has one final check for detecting ropes. Notice that it’s offset to the left, meaning jumping left towards a rope will grab it faster than jumping towards the right.

Fun Fact! When I was a kid I was sure you had to hold up on the joystick just as you reached the rope, otherwise you jumped through it and fell to your death. I only learned much later in life that the player actually automatically grabs the rope. Had I known that then it would’ve saved me pain playing with those horrible, horrible Tandy joysticks.

Rope Quirks

The interesting thing about the rope detection is that it only checks whether it touches white pixels on the clean buffer. It doesn’t matter if the pixels are from a vertical or horizontal rope.

Horizontal Ropes

For horizontal rope traversal, the game relies on the fact that if you press and hold left or right while in a climbing state, the player will hang off the side and then fall off.

In the code, shimmying across a horizontal rope is actually the player repeatedly grabbing a rope, moving to the side, falling off, and then re-grabbing before gravity starts to affect the player’s vertical position.

I thought this was a pretty clever way to introduce a fun traversal mechanism with existing functionality.

More Rope Quirks (last time I swear)

When the game draws objects, it blends pixels together. So overlapping the player over objects and the background appears like so:

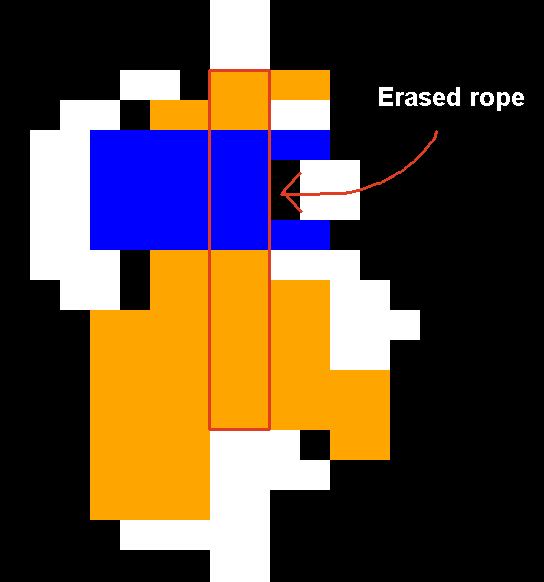

This actually also happens with ropes:

To prevent this, the game erases the rope behind the player, so that the sprite appears correctly.

But it only erases the rope when the player is in the climb state. You can see the player and rope blending together when jumping on or off.

Fun With Collisions

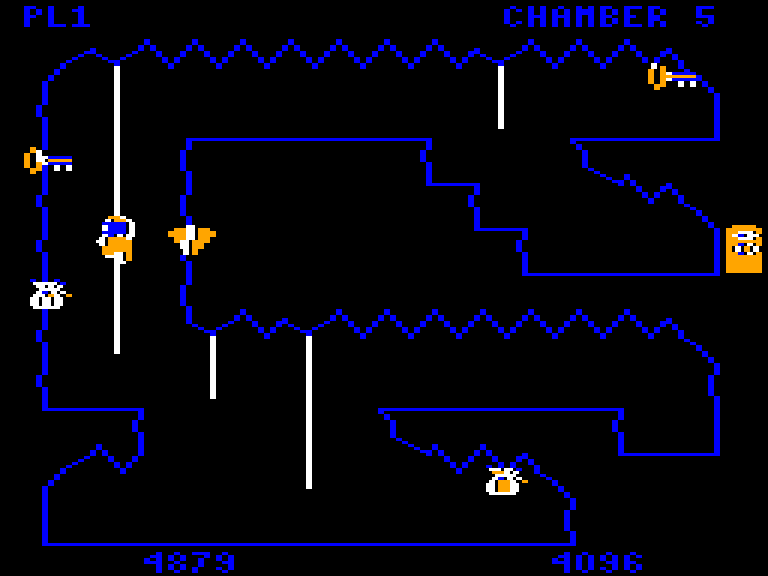

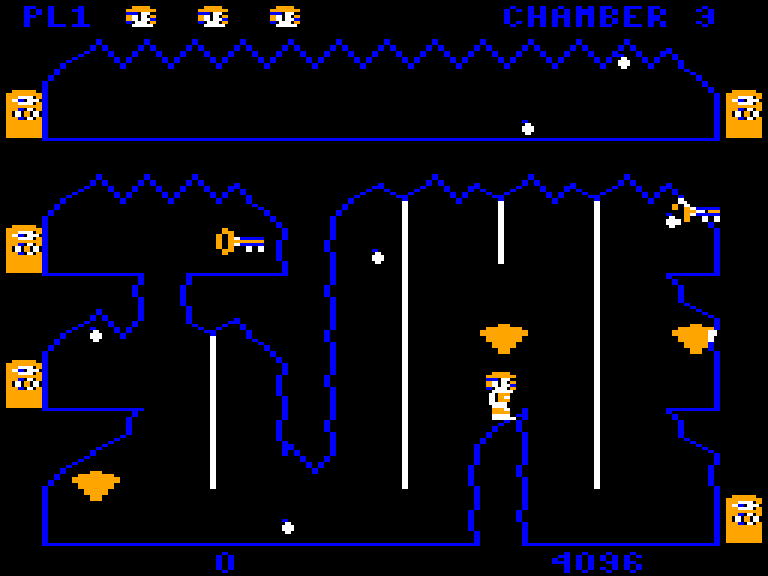

Something you don’t see often with games of the era, Downland’s per-pixel collision detection lets the player jump at a wall and land on a ledge:

This is really fun to do and is actually a technique that the player needs to master because in chamber 5 there is a key needs to be picked up this way.

It also lets the player bypass obstacles, like in chamber 3 where they can avoid the tricky rope jumps by just jumping across on the rock.

Porting Considerations

The large memory requirements of the frame and clean buffers made porting Downland on certain retro consoles an interesting challenge. While platforms like the Sega Genesis, 32X, Saturn, and Dreamcast have enough memory to hold both the frame and clean buffers in memory, older platforms like the Sega Master System, SG-1000, ColecoVision, and NES do not. The ports to those older platforms had to eschew the frame buffer, which was also used for object collision detection, and use pre-drawn clean buffers stored in ROM. These pre-drawn clean buffers take up significant ROM space (12 screens at 6k each). At the price ROMs cost back in the early 1980’s I don’t think a version of the game on those platforms would’ve been viable.

Side note: The Sega Master System port of Downland stores the clean buffers in ROM, but it turns out it doesn’t have to. The console has 8k of memory. The original port I did used over 2k of ram for game variables, not leaving enough space for a clean buffer. The rom wound up to be 128k in size. However, the SG-1000 port I did after heavily optimized memory usage and dropped it to less than 1k.. So if I wanted to, I could revisit the SMS version to use a clean buffer, removing the need to store all the per-room clean buffers in ROM, making the game smaller. But I’m lazy so who knows if ever that’ll happen!

Next Time

And that’s it for background collisions. While memory hungry, it provides some fun and unique gameplay features. Next time we’ll look at how the frame and clean buffers are used for player-object collisions.

Leave a Reply